(At least) 4 Xs that aren't UX

And why the original is still the best. Plus: Minecraft robot studies

As I’ve argued before, user experience isn’t an immature field. The name was coined almost 30 years ago, and professionals have been doing roughly similar kinds of work for even longer. Neither did it appear in a vacuum. Its older siblings human factors and human-computer interaction have been around since at least the 40s.

Nevertheless, our field acts like an immature one when it gets caught up in endless arguments over words. We have strong opinions about whether UX/UI is an acceptable alternative combination of letters in one’s job title, and whether or not there’s a meaningful difference between user experience research and user research or user testing and usability testing.

But the grandfather of all these debates centers on the very name of the field itself.

The problem with “users”

Much of the controversy surrounds the first half of the term: “user.”

As Edward Tufte famously observed, “There are only two industries that refer to their customers as ‘users’, one is of course IT, the other is the illegal drugs trade.” And in the wake of books (like Alone Together) and documentaries (like The Social Dilemma) bringing to light the habit-forming and harmful potential of technology, the parallel meanings of “user” might seem eerie.

While this alternative meaning of “user” lives on, it’s no longer the primary definition. In fact, the word has been more common in technology than in drug contexts since 1959. This graph from Google’s Ngram Viewer, which analyzes the incidence of words in books, shows how the meaning has changed over the years, with the “phone” context steadily climbing and ultimately overtaking “drugs” and “computer” by 2010.

Nevertheless, this hasn’t stopped opponents from calling the word reductive and limiting with its bad connotations. Some point instead to its origin in the days of mainframe computers, when the primary user, a skilled technician, would act on behalf of a less-technical “end-user” who requested and consumed the output. Thus, saying “users” or “end-users” could give the impression that they are “faceless automatons who will accept what is given and do what they are told, brain optional.”1

No less a figure than Don Norman himself, who coined the phrase in 1993, has argued the term is derogatory: “One of the horrible words we use is ‘users.’ I am on a crusade to get rid of the word ‘users.’ I would prefer to call them ‘people.’”2

This wouldn’t be the first time Norman has split hairs on a term he popularized. His distinction between affordances (on physical objects) and signifiers (in digital interfaces) never really caught on.

“Humans” is not specific enough

Norman’s far from alone. But despite his crusade, the consultancy he co-founded, Nielsen Norman Group, still uses the word frequently, with more than 20K results for “user” across their site. And for good reason! The First Rule of Usability (discussed at length in last month’s issue) would have a very different meaning if “user” were replaced with “people.”

Saying that we study “people” or “humans”3 conveys less information than saying we study “users.” “People” suggests nothing at all about the context in which we study them: interactions with systems.

Some try to bridge that gap by turning it into a longer phrase, such as, “people who use our product”—a mouthful for which we already have a single word. But even that would be better than creating new terms from whole cloth, like “experiencer.”

Other tech-specific terms are worse

Instruction manuals offer an alternative: “operator.” Aside from having twice as many syllables, this word isn’t free from negative connotations. Nor is it above any accusation of implying facelessness. Instead of acting upon a system, the user becomes an operation in a mathematical formula.

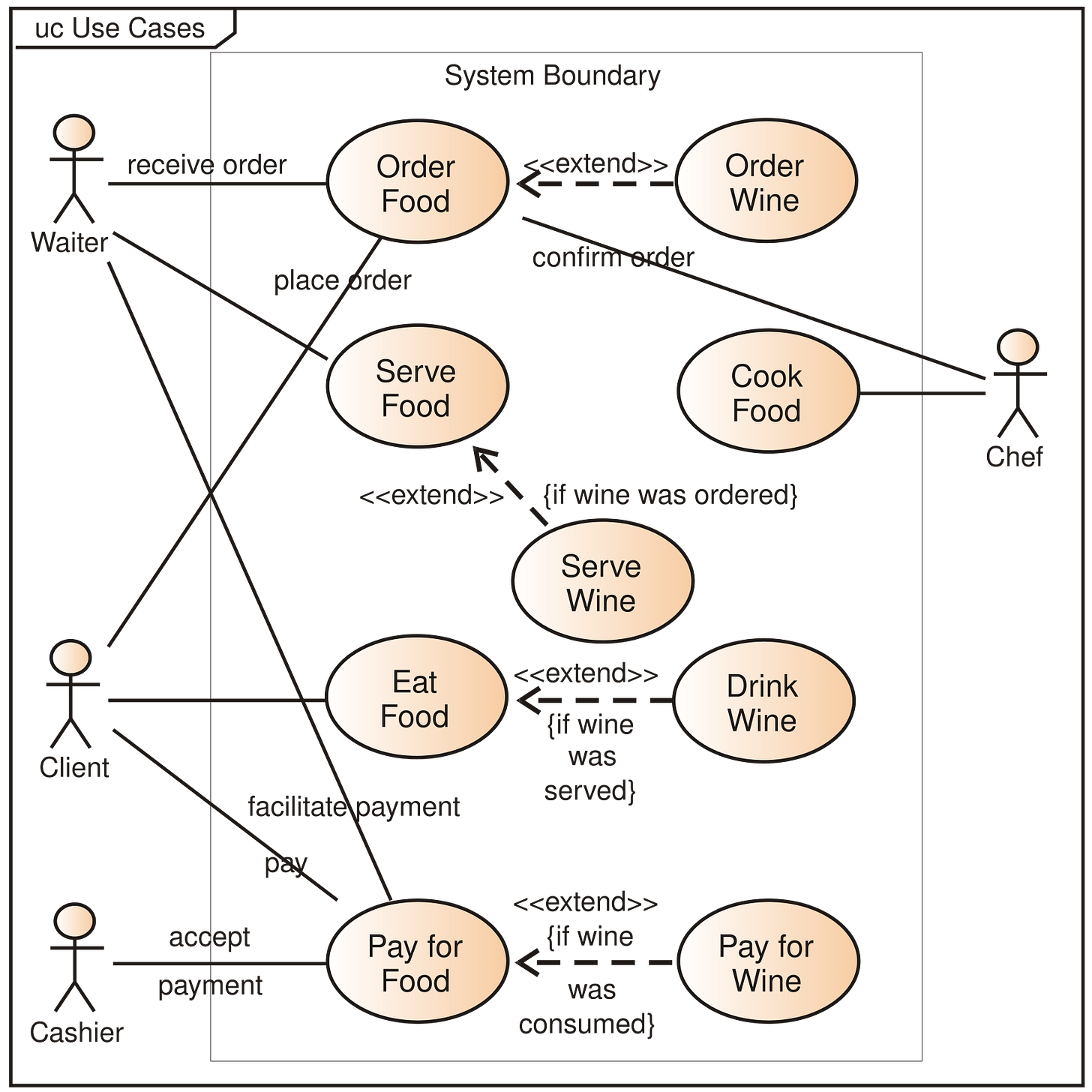

Others have proposed using the word “actor,” to emphasize that the user is actively engaging with the system to facilitate some goal. This option has some precedent in software engineering, which distinguishes “users” (as a general group) from “actors” (as specific instances of users) in UML use case diagrams. But far more people will associate “actor” with a stage or film performer than they will “user” with narcotics. And in everyday language, acting often means behaving falsely.

Aside from some weird non-starters like “wranglers” and “biots”, that doesn’t leave a lot of tech-specific words. And most of them, like “agent,” already have widely-used and accepted meaning.

Plus, “agent experience” could easily be confused with a more specific UX subtopic focused on customer support representatives—which brings us to our next category of bad alternatives.

Getting too specific isn’t better

A favorite of “customer-obsessed” organizations, many prefer to rebrand UX as CX or “customer experience.”

Sometimes, CX is even said to have a broader scope than UX. In this view, CX would encompass the end-to-end experience of every interaction, direct or indirect, that a customer can have with a brand. In truth, this is an artificial distinction, since industry definitions of UX, including Norman’s own, have long included non-digital experiences.

Nevertheless, “customers” aren’t always interchangeable with “users.”

In many cases—such as enterprise software, children’s products, and thermostats for rental units—the individual making the purchase may rarely or never use the product. Other products, like Spotify and YouTube, have both paying customers and freemium-tier users. And for most organizations, understanding the experience of prospects who don’t yet have a relationship with the company can be incredibly valuable. Designing with only customers in mind may not benefit all users, and may ultimately stunt company growth.

Even for organizations whose users might be best described with a more specific name, the terms CX and its siblings “employee experience” (EX) and “member experience” (MX) fail to accurately reflect our practice’s place in a broader discipline.

A large part of a researcher’s job is advocating for UX and growing the organization’s maturity—a task only made more difficult when the field goes by a dozen different names. We educate and collaborate with many partners from diverse disciplines, many of whom have little familiarity with UX.

When those colleagues move on to new roles, they may not make the connection that CX, AX, EX, or MX does the same kind of work.

The best option—or at least, the best bad option

Norman’s right: it’s important to remember that the people we study are people. But he and other critics are wrong that “user” is a derogatory term that dehumanizes them. It’s merely descriptive, in the same way that “driver” and “musician” are useful labels to identify a specific subset of humans.

We’ve grasped for alternatives in the 16 years since Norman first made the argument, and have unfortunately come up short. “People” isn’t specific enough, and “customer” is often too specific. The others—like “operator,” “actor,” “agent,” and “experiencer”—are either too weird, or suffer from the same problems that “user” does.

Once again, we can learn from the history of other fields. Research psychologists have long called the people in their studies “subjects” or “participants”—both of which have had similar controversies to this one surrounding “user.”

Today, the American Psychological Association, in its reporting style guidelines, encourages scientists to refer to these people with more specific terms (such as “college students” or “children”) whenever appropriate, while acknowledging that “subjects” and “participants” are commonly-understood and justifiable general terms. Above all, they say to “write about the people who participated in your work in a way that acknowledges their contributions and agency.”

We can, and should, do the same.

Your next usability study might take place in Minecraft

As part of a recent talk with the Human Systems Engineering students at ASU, I got a tour of one of the labs and learned about some of the research going on there.

One thing that surprised me was the number of simulations this lab ran in custom environments of the popular game Minecraft:

[R]esearchers recently pilot tested the Minecraft test bed at a virtual hackathon in June, bringing together more than 100 performers from over 20 organizations. Due to COVID-19, the team pivoted from a planned in-person event to an entirely virtual exercise…

“Using Minecraft for the simulated task environment allows us to design complex and highly dynamic tasks,” PhD student Verica Buchanan said.

Rather than build a prototype robot on an elaborate testing stage, they can have participants try an experience with a virtual robot in a programmed scenario. And it works well in our remote world!

Eventually, the robot will need to be built and tested, but this is a clever way to iterate on an MVP—and it comes from our friends in academia.

from Don't call me a 'consumer' or an 'end-user' by Galen Gruman (2012)

Finally, an article I’ve been waiting for.